How I Beat the Snot Out of Myself

Pixies - Surfer Rosa. The final part of the Allergy Trilogy.

Hi, you can read parts 1 and 2 of the Allergy Trilogy here and here. Not needed to follow part 3, but they add more context.

June 16, 1995

My allergies are out of control.

My eyes look like I just smoked five joints, then lost a boxing match. Twin bloodshot orbs, swollen half-shut. My nose is a snot faucet without a shutoff valve, and the roof of my mouth is raw from perpetually scratching it with the tip of my tongue, and when that doesn’t do the trick, a chopstick. Or a butter knife.

I’ve been living on ALM Farms in Sooke, British Columbia, on the southern coast of Vancouver Island for about two months. When I arrived, I expected I might have a histaminic response to my new rural surroundings.

But I thought that over time my body would acclimate, that this exposure therapy would prove that it could exist just fine in close proximity to twelve ducks, nine guinea fowl, a dozen chickens, several cats, and ten acres of dirt, soil, grasses, and trees. AKA, farmland.

My Western medicines barely make a difference. Benadryl makes me drowsy and unable to focus. The sublingual homeopathic drops I administer every two hours may as well be droppers of water for all the help they provide. Powering through — my only option it seems — turns me into an unpleasant person. I truly love all the new friends I’ve made at the farm; I don’t want to appear like a stereotypical ugly American. It’s a lot of responsibility, as the only US resident on the farm. Up until now, I’ve mostly pulled it off (I think), but I can feel my inner needy child beginning to whine and pout.

Canadians are the nicest people in the world. This is not a stereotype. I only have Western British Columbia to go from at this point, but I’ve been welcomed into the small but tight-knit farming community here with open arms (and garden-gloved hands). No one gives me shit when I have to end my workday early due to non-stop sneezing and my eyes swelling nearly shut.

One of the farm’s regular visitors, Sandy, an herbalist, suggests I drink stinging nettle tea. There’s a ton growing on the farm, so it’s easy to make.

I imbibe gallons of it. I can’t tell if it does anything. The only definitive response is having to pee twice as often.

I’m desperate, so I go to the source and run my hands through the nettle leaves. I’ve prepared a poultice of chewed-up comfrey leaf to rub into my hands to reduce the stinging. Mary Alice Johnson, the farm owner, taught me that where something “poisonous” grows, the “antidote” can be found nearby.

After a week of intentional nettle stinging, the pain reduces to a strong tingling sensation and I no longer need to use the comfrey. But other than making me feel like a badass, it does very little to reduce my allergies.

I’m not religious, but every morning I wake up and write impassioned pleadings in my journal to God/Buddha/King Histamine to make these horrific allergies disappear. And if this isn’t possible, to at least reduce them to a manageable level.

I’m only able to last a couple of hours preparing vegetable beds, planting seedlings, setting irrigation, and picking fruit for the Saturday market. Normal workdays are not excessive; we’re expected to work from 10am to 6pm on weekdays and from 6am to 3pm on weekends.

I’m not pulling my weight and feel awful.

I don’t want to go home, but it’s starting to feel like I have no other choice. Mary Alice depends on all of us to keep the farm in working order and I’ve been here long enough to be expected to take on more of a leadership role for the newer volunteer workers.

I’m especially bummed because as a pampered city boy my entire life, I thought I’d adapted to life as a small-town WWOOFer remarkably well, considering a year prior I couldn’t pick out a broccoli plant from a tomato plant if my life depended on it.

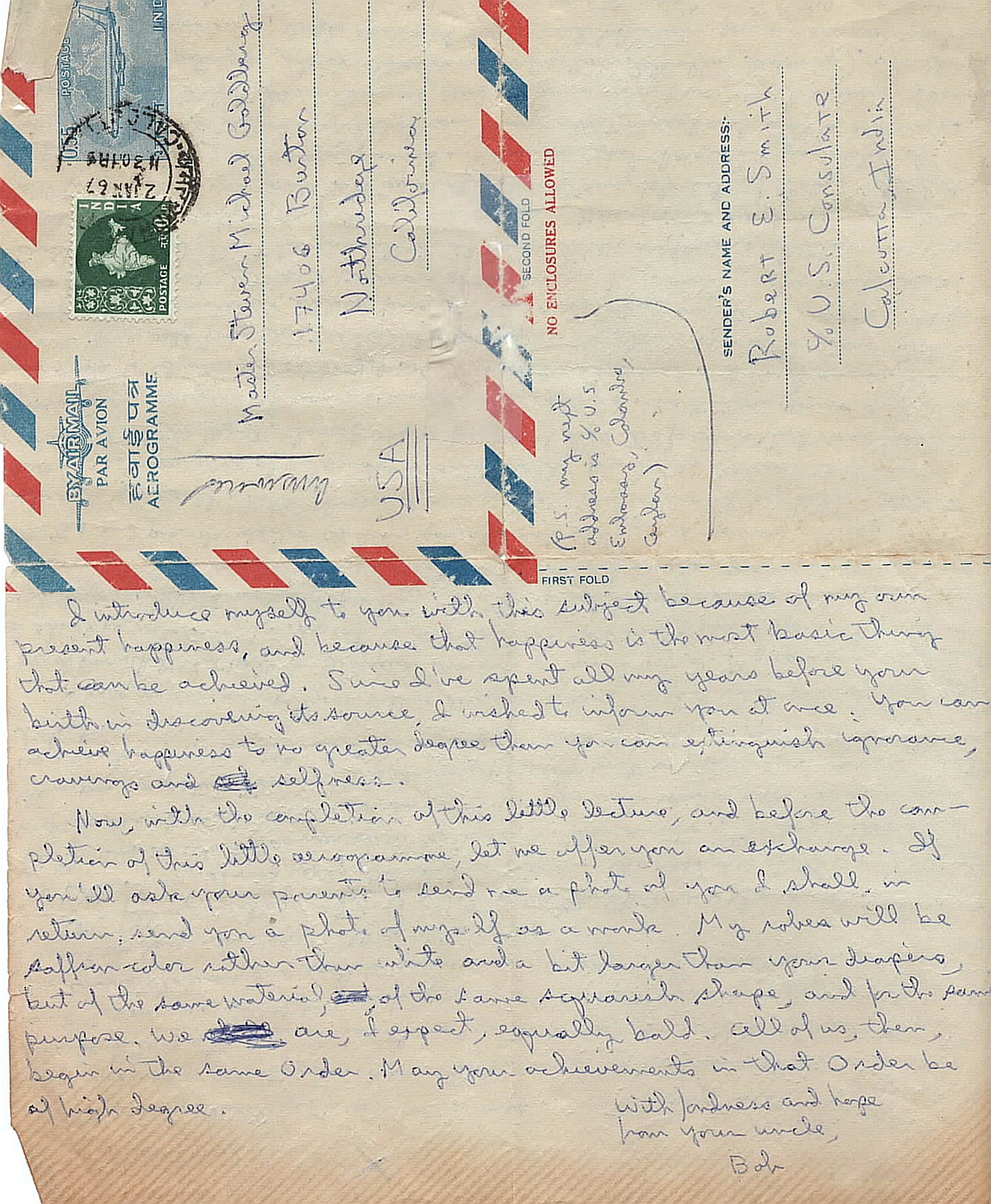

December 19, 1966

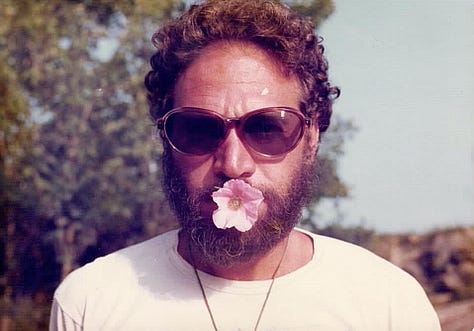

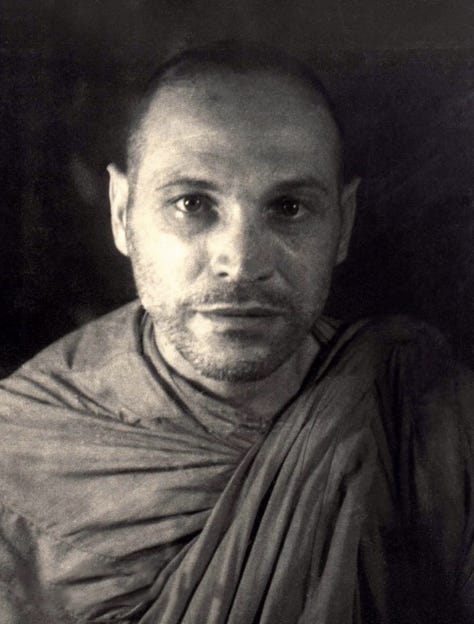

A boy is born. A man is reborn. The boy is given the name Steven Michael Goldberg. The man, Robert E. Smith, is ordained as a Theravadan Buddhist monk in Calcutta, India. The man is Steven’s uncle.

Robert writes his nephew an aerogramme letter, welcoming him into the family, into the world. He jokes how the two of them have co-emerged — bald and with only the most basic of needs. He warns his new nephew not to get caught up in the false promises of accumulation, of the capitalistic nature that cravings and comparison bring. How living a life simply and attentively, without encumbrances can bring exquisite joy.

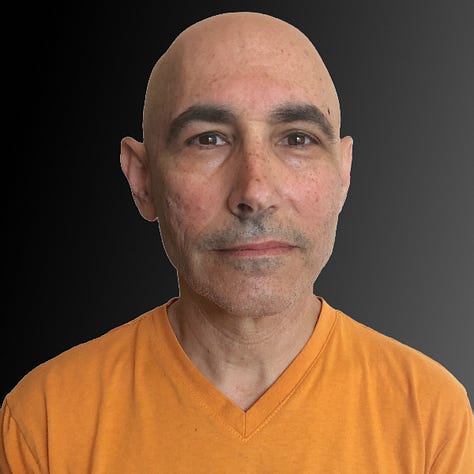

Throughout his young life, Steve will be told over and over, from great aunts and uncles, from grandparents and cousins, how much he resembles his uncle Bob, both physically and temperamentally.

“Doesn’t Stevie have Bob’s deep, sad eyes?” “Bob used to sit in the corner reading a book just like Stevie is doing!” “Such a shy kid! A spitting image of his uncle!”

Steve wonders how he can be so much like this person that he’s never met. That he’s never seen. Why can’t he simply be like himself?

Steve flips through stacks of photo albums at his Nana Betty and Papa Al’s apartment. Staring intently at sepia-tinged images of his uncle as a small boy, a young kid, a teen, a college student, and a man in his early 20s. He tries to see the resemblance. He cannot see the resemblance.

It will take a couple of decades, not until the fall of 1988, after his uncle Bob’s tragic death at age 49 while traveling from Columbo, Sri Lanka to the US to see his family for the first time in more than a decade, before Steve finally sees the resemblance.

May 30, 1993

Steve did not read the letter his uncle wrote to him on the day of his birth until May 30, 1993, at age 26.

Several months after his uncle’s death, Steve’s grandfather Alan received a letter in the mail from Vancouver Island, Canada, from a person he did not know, with the singular name Hum.

Hum, whose birth name was Stewart Murphy, had met Robert while traveling in Israel during the early 60s. They’d immediately hit it off, bonding over a shared love of music and literature. Specifically, they shared a love for the beat writers. Ginsberg and Kerouac as well as novelist Thomas Pynchon.

It was their contrasting temperaments that made Bob and Stewart such great travel companions and friends. Stewart was the tall, red-headed Irish prankster to Bob’s shorter, olive-complected, dark-haired brooder with a quiet adventurous spirit.

Both Robert and Stewart had open-ended travel plans and soon decided to journey together through Afghanistan and Pakistan, finally settling in India. This was around 1963-1964.

For the next two years, they both stayed in India, studying Buddhism. Eventually, they both decided they wanted to take their practice deeper.

Stewart and Robert became ordained as monks on December 19, 1966. Stewart would change his name to Hum, which according to my web research, means something different in Hinduism, Sanskrit, Marathi, Jainism, Prakrit, and Hindi. One definition I found that I especially like is that Hum loosely translates as “cipher for understanding the Truth.”

Robert eventually would be given the name Samanera Bodhesako. Samanera essentially means novice male monastic. Bodhesako, I have not found a clear answer. Bodhe might be wisdom. Sako, though, doesn’t translate into anything in Pali or Sanskrit. Perhaps a reader might have an idea.

Hum left the monastic life after a couple of years and returned to his home country of Canada in the early ‘70s, where he’s been living ever since.

Hum and Steve’s grandfather continued corresponding via letters for five years, until Alan’s death in 1993. It wasn’t until Steve went through his Papa’s belongings that he found the letters Hum had written.

It was via these letters that Steve learned of the man who had been his uncle’s best friend and his grandpa’s new friend. He wrote to Hum to inform him of the death of Al Smith and to introduce himself.

Within two weeks, Steve received the first of many letters from Hum. At the end of the first letter, Hum wrote: “I live in a hand-made shack in the Sooke mountains on Vancouver Island. No, electricity, no running water. If you ever make it up here, you have a place to stay.”

A year later, Steve quit his job as an assistant video editor and drove up from San Francisco to Vancouver Island to meet The Man From U.N.C.L.E.

June 5, 1994

I’ve never been to Canada before. I’ve never been anywhere, really. I’m 27 and the only country I’ve ever visited is Mexico. The furthest I’ve ever flown is from Los Angeles to New York. And that was when I was 10, with my Nana Muriel to see our cousins.

Other than meeting the man who knew my mysterious uncle better than anyone else, I’m hoping this trip will expose me to new sights, but more importantly, new experiences.

After stopping in Portland, Oregon to visit friends from college, I drive to Seattle and take the car ferry to Victoria, British Columbia.

Sooke, where Hum lives, is a 45-minute drive from Victoria, due southwest. I find the town easily as there’s essentially one main coastal highway.

I turn right onto a narrow street that quickly becomes a 1-lane dirt road. The only directions I have are a piece of paper I copied from Hum’s last letter telling me to take the dirt road until I see three pigs in a pen on the left. There will be a place to park my truck 500 feet past the pigs. I trust I have the correct information. Hum has no phone; Google Maps won’t exist for at least another decade. Roads like this are not in my Thomas Guide.

I find the spot, park, then enter the combination for the lock on the gate. It opens. It’s 4pm. I grab my camping backpack which has everything I’ve brought with me and trudge up the hill. Hum has attached bright red ribbons to trees at any places where it might be unclear which way to turn on the trail. After about 45 minutes, I come to a small clearing. I find the hut.

“It only looks like it’s about to fall over,” a voice calls out from behind me. I turn and see a muscular man of about 50 with a full red beard and matching long red hair that’s thinning on top. He’s carrying two giant jugs of water.

Hum is dressed in purple running shorts and a banana-yellow Nike tank top. It’s a lot of strong hues all at once, especially in this lush, green wooded setting.

Hum sets down the water, I put my pack down and we have a long embrace.

We bond immediately.

As Hum walks me over to another, more traditionally built structure (above), where I will be staying during my visit, he shows me how to find my way around the trails up in these mountains. It’s easy to get lost when it’s getting dark, so he offers to walk me back after dinner this first night.

“And don’t worry, the grizzly bears out here are vegetarian!” Hum snorts when he laughs and I catch a playful glint in his blue eyes.

The next day is packed with activities. Since I have a car, I can take Hum to see friends he doesn’t normally visit, as it’s too far. Though he does jog 4 miles each way to the nearest market and drug store for supplies a couple of times a week.

The first thing we do on day two, after a breakfast of oatmeal and blueberries cooked on a propane stove, is drive over to his good friend Mary Alice’s farm. She has been donating produce to Hum for a few years now, and in return, Hum helps work the land for a couple of hours. When we arrive at ALM Farms ten minutes later, I’m blown away. I’ve seen mono-crop farms from the side of the road in California, but I’ve never stepped foot on one. And ALM is about as opposite from mono-crop as you can get.

There’s corn, leeks, kale, tomatoes, peppers, squash, garlic, and at least a dozen other vegetable varieties. Not to mention the apple trees, the pear trees, the kiwi, the fig trees. And a giant herb garden that is being managed by three home-schooled sisters that live down the road. There are ducks and chickens in fenced-in areas, and a couple of cats roaming.

Hum introduces me to Mary Alice, who then introduces Hum and I to a half-dozen young farm workers, a couple of who live at the farm, the others are local volunteers.

Everyone is incredibly friendly and is more than happy to explain to us what they are doing — their process for planting or weeding or harvesting. If I were working that hard, I imagine I might be annoyed having to stop to talk to strangers when I know I have so much to get done. The lack of bother expressed by the folks on the farm is appealing but difficult for me to grasp.

We are invited to have lunch with the crew. Sue, one of the workers, who I will learn is a WWOOFer, invites me to help harvest lettuce and edible flowers for the salad.

We pick a variety of lettuces, then in a separate bowl, collect nasturtium flowers, calendula, and borage. My mind is being blown every other minute. I can feel in my bones that this is something I need to do. That I need to get away from the city. And learn how to live off the land.

The Farm

Sue explained to me that WWOOF stood for World-Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms. That she’d been traveling across Canada for three months, WWOOFing at various farms. All WWOOF farms are educational farms that are required to provide free room and board.

Of all the farms Sue had worked at, ALM was the best.

“You should totally do this!” Sue said after I told her how much farm work both appealed to and scared me. I was so green at being green — I thought I would be starting with negative points. “No, you’ll be fine. There are lots of newbies.”

Before we left the farm for the day, I got Mary Alice’s business card and told her I would be in touch about WWOOFing at ALM the following year.

ALM Farm, was (and is) a 10-acre organic farm providing a wide variety of fruits, vegetables, and herbs to local farmer’s markets, restaurants, and residents.

“The name ALM was chosen by my husband Jan for his consulting company. Jan traveled widely and spent time in countries that had large Muslim populations. “ALM” is Arabic for Alif Lem Mim which stands for the Beginning, the Middle and the End. I see farming as cycles and seasons so adopted the same name. ” - Mary Alice Johnson, Founder ALM Organic Farm

In 1995, there were four options for WWOOFers living on the farm.

The Barn. The top level of the barn, above the rototiller and other garden tools, was large but only had one wall and a sloped roof for weather protection. And an extension cord running up from below for electricity.

The “little house”: an A-framed structure with a tiny loft, a wood-burning stove, and the only place on the farm with running water not connected to irrigation in the fields. It did have electricity and was the spot we often hung out in on colder nights.

A 25-foot trailer. The sort of trailer that would be attached to a truck but without the truck part.

The Bender. A circular wooden raised platform with a 6-inch lip about 12 feet in diameter. A dozen or so bamboo poles, placed into the lip and bent into a bow shape are tied at the top to create a dome-like frame. Giant blue tarps are bungeed together to protect the bender from the elements. It has two small cut-out windows. No electricity. No furniture.

When I arrived at the farm in April 1995, both the barn and little house were occupied by other WWOOFers. The Bender was in the process of repair, so I got the trailer. Total score for me, as it had electricity, a mini-fridge, and was the closest spot to the two outhouses. Did I mention that there were no bathrooms on the farm? That took a little while to get used to.

June 17, 1995

I’m able to last only two hours today.

It was my job to harvest the potatoes — usually one of my favorite activities on the farm. It’s like going easter-egg hunting, pulling purple, yellow, and red potatoes from the soil like endless birthday presents.

But my snot faucet won’t shut off and my head feels like an anchor is smashing into it from above.

I hesitantly tell Mary Alice that I need to lie down for a couple of hours to try and recover.

I crawl back to my trailer and fall flat on my bed, completely defeated. I have tried everything possible, but my body simply won’t allow me to exist on a farm. I get up, pop a Benadryl and grab my boombox.

When times get hard like this I do what I always do. I put on music.

Loud music. Cathartic music. Today that music is the Pixies’ album Surfer Rosa.

I air drum the mattress along with drummer David Lovering, letting Black Francis’ and Kim Deal’s iconic growls dig into my “Bone Machine.” When “Break My Body” comes on, it feels personal as if the farm is literally trying to break my body.

The next thing I know, I’ve pulled out my bongos and set them between my knees. When “Broken Face” begins, I’m bashing on the skins with all the force I can muster in my weakened state. I‘m teetering in the space between passing out and an out-of-body experience.

I’m beating out my profound disappointment — for having come to another country, for going way outside my comfort zone, for finally recognizing and then following what felt right to me deep down — and now my body is breaking and I’m going to have to go home.

I can feel the disappointment turning to anger, my fingers, my palms smacking the skins of the bongos with even more whipping force. The rhythms are barreling through me and I am no longer a person but a vessel, a conduit of percussive expression. I am aware, in a distant sense, that my fingers are burning, that the constant beating is turning my palms to bloody meat pads.

But it doesn’t feel like pain, it feels like energy. Like life force. Like release.

As “Where Is My Mind?” plays, sweat is pouring off me in rivulets. I can feel it dripping from my eyebrows, my chin, my armpits, my elbows. I’m playing and playing and playing and I’m no longer inside the trailer. I’m no longer on the farm. I’m no longer in Sooke, in British Columbia, in Canada, on planet Earth.

I’m playing for all the people I’ve never let myself become, for all the places I’ve never traveled, for all the experiences I’ve avoided or cut short, whether out of fear, ignorance or feeling like an imposter.

I’m no longer drumming to the music anymore. I’m playing at a post-music speed. David Lovering couldn’t keep up with me if he wanted to. I’m a battering ram. I’m a machine gun. I’m an explosion.

When the driving song “Vamos” comes on, both I and the Pixies are one and the same again. “Vamos” in Spanish means “Let’s go.” And when the song ends, I do the opposite of what Black Francis demands.

I stop.

My hands and arms rise straight up in the air as if being summoned by the sky. My entire body is buzzing, electric, but not in a high-voltage way, more vibrational. The music stops. All sound stops.

Except for one sound.

My breath.

My breath is deep and slow and insistent. I feel it entering and exiting my nostrils. I feel it from the bottom of my feet to the top of my head.

My breath is full and clear and present. My breath is Gigantic. My breath is a big, big love.

I slowly stand up, reach forward, open the door to my trailer, put on my work boots, take a long look at the almond tree in front of me thick with white flowers, and head off to join the others in the field.

And that, my friends, is how I beat the snot out of myself.

I tried to pack a lot of life moments into this — hopefully, it all flows okay for you.

Have you had any out-of-body experiences that were born from completely giving up or giving in?

I don’t have much in the way of conversation starter points; I just would love to know your general reactions.

As always, thanks for reading. You rock!

Steve

What a great experience you had working on the farm! I mean, except for the excruciating allergies. But besides that, I think it’s pretty cool that you had a love for working in the dirt at such a young age. I didn’t come to it until recently.

I have seasonal allergies as well, but they are concentrated to March and April. Before I discovered Claritin-D, life was pretty miserable during those months. I also had tried all sorts of herbal tinctures and found that they didn’t work.

Also, love that photo of your uncle in the 70s with his sunglasses on. What a time capsule of that era! I love and miss film photography.

I enjoyed reading this. I thought my allergies were bad but this is something else -- I feel for you. Glad you found a way to keep them more or less at bay (or, at least, distract them with something enjoyable). A case of “good for your mind, body, and soul”.